Photos by Tyler Polk

Two people wearing nose masks at the Clean Air Rally on March 20, 2018.

Allegheny County Air Has Improved, But It Is Still Mired In Major Problems

Since moving to Natrona Heights, Donna Frederick, says she has had to wash her car at least three times a week to remove dust since moving across the street from one of the region’s worst polluters.

Marti Blake, a resident of Springdale says coal dust comes into her house from the toxic Cheswick Generating Station even with her windows closed.

These two people all live next to facilities listed in the Toxic 10, a list of the ten most toxic air polluters in Allegheny County. The periodic list shows while air is better in this region after the closure of many steel mills and other polluters, it remains among the worst in America.

The first Toxic 10 list was released in 2015 by PennEnvironment and it used information from 2013 and 2014 to compile the rankings. The second toxic 10 report was released in February, using data from 2016 to report on the problem. You can find the latest report at toxicten.org.

“The reaction was really strong, but the Allegheny County Health Department and the facilities were not so much a fan of the report,” said Zachary Barber, PennEnvironment’s Western Pennsylvania Field Organizer.

“There’s a lot of groups doing air quality work in Pittsburgh, but this was the first time someone provided a roadmap what the pollution landscape looks like”.

“We appreciate PennEnvironment’s commentary regarding air quality in our county. It is important to note that some releases of toxins are allowed under EPA standards, and they are not considered violations,” said Karen Hacker, Director of the Allegheny County Health Department, in a February statement.

Self-Reported Data

Zachary Barber from Penn Environment, talking to people who attended the rally for clean air on March 20th, 2018.

The Toxic 10 is built using databases from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). These databases use self-reported data on what toxins were released, how much in pure tonnage, and how bad a chemical is.

“We looked at how much they put out multiplied by how bad it is to get the toxicity score”, said Barber. “We looked through each facility for everything they put out and added all together to get the overall score for the facility.”

One in three of the 1.2 million people living in Allegheny County live within three miles of the facilities listed in the 2015 report and Barber says that there are similar numbers for the newest Toxic 10 report.

“They see, smell, and taste what’s in the air and understand the entire range of issues, from the quality of living and health to property impacts,” said Barber.

Pollution in Natrona Heights

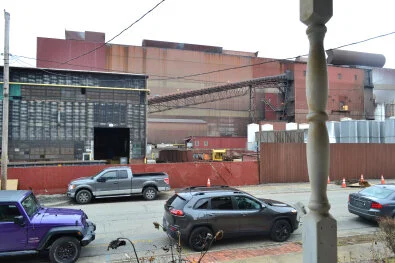

A sign hanging up outside Donna Frederick of Natrona Heights house. Her house is located across the street from ATI Flat Rolled Products – Brackenridge.

When Donna Frederick of Natrona Heights bought her house in 2007, she figured she would rather live next to the noise of the steel mill than next to drug dealers she had lived close to in the past.

“Through the years I found out that, it would be better to live next to drug dealers, than live next to ATI,” she said.

Frederick has lived in Natrona Heights for ten years, right across the street of ATI Flat Rolled Products, also known as Allegheny Ludlum. The facility was ranked number two on the latest Toxic 10 report.

The Toxic 10 report found Chromium, Cobalt, Hydrogen Flouride, Lead, Manganese, and Nickel compounds coming from the plant. These substances are on the EPA’s list of hazardous air pollutants and are suspected to cause cancer and other health effects.

“We take our responsibility to the communities in which we operate very seriously, including those in Western Pennsylvania,” said Scott Minder, a spokesperson for ATI. “We now have the best available pollution control equipment installed on our Brackenridge HRPF and melt shop facilities.”

Donna Frederick and her husband, Albert, holding the sign and wearing face masks.

“I’ve taken multiple pictures and videos [of the results from the facility’s emissions],” said Frederick. “I’ve had GASP (Group Against Smog and Pollution), take samples of my soil and red residue in my bird bath”.

Recently, Frederick had samples tested from her soil by ALS Environmental, the report found amounts of mercury, arsenic, barium, cadmium, chromium, and lead. These are two hazardous air pollutants according to the EPA.

“We have a swimming pool, and because of the residue getting into the filter, we have to clean that every day,” said Frederick.

Living next to the plant has left her house covered in a white ash-like residue, and the smells of rotten eggs, wires burning makes it hard for her to sit out her porch.

“It’s sad that you can’t sit on your porch and have coffee unless you want your lungs to hurt,” said Fredrick. “This area is known for rentals, so people would buy the houses not knowing [about the pollution]”.

Her neighbor, Rebecca Miller, said the smells forced her to leave her house on two occasions.

“The first time, it made me dizzy, I went shopping and came back home and I really noticed it”, said Miller. “Another time it was a burning feeling in my throat and my eyes. I smell it often, but it’s never been like those two times, but it’s still strong.”

According to the Allegheny County Title V Operating Permit Status Report, Allegheny Ludlum has never been issued a Title V permit in its history.

A Title V permit is required by major sources of pollution and certain facilities for these sources. The permits are enforced federally and can add additional requirements to facilities such as emissions fees and compliance reviews.

According to a spokesperson from the Allegheny County Health Department, the facility was in the draft permit stage and found new information about emissions they were not aware of and have made new limits since then. Currently, the Health Department is reviewing comments from a public meeting from December 19th, 2017.

Pollution in Springdale

Randy Francisco (left) and Marti Blake (right) at the Clean Air Rally on March 20th, 2018.

After selling her house in the North Hills in 1990, Marti Blake had two weeks to find a house for her and her two children, then ages three and six. She moved into her house in Springdale across the street from the Cheswick Generation Station, a coal-fired power plant.

Penn Environment’s Toxic 10 list ranked the plant as the number one Industrial air polluter in Allegheny County. The report found Arsenic, Chromium, Dioxin, Hydrochloric Acid, Hydrogen Flouride, Lead, Manganese, Mercury and Nickel compounds in its emissions.

“The air surrounding NRG’s Cheswick Generation Station meets the requirements and emissions from Cheswick are far below its permit limits and is doing much better than its required to do under its current Title V Air permit,” said David Gaier, a spokesperson for NRG.

The view outside Marti Blake’s house in Springdale. This the stacker (left) and the scrubber (right) of the Cheswick Generation Station.

“My mother told me, Marti, you’d better get out of there or you’re going to get cancer,” said Blake. “My mother was very smart, but at the time, I had nowhere to go.”

Marti now has asthma and must take an allergy shot every four days. Four years ago she was diagnosed with Melanoma.

While there is no medical relationship known between health and the plant, according to a 2013 study from the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Allegheny County is in the top 2 percent of cancer rate in the United States.

“I had to have surgery, on my arm, and had lymph nodes removed,” said Blake. I have to go to a dermatologist to get a full body scan every six months to make sure nothing else is popping up.

Coal dust from the coal plant, comes into her home, even when the windows are closed. She cleans her house every spring and one year, it went from bright sunlight to darkness for five minutes. A man who was across the street watching her apologized for the coal dust cloud ruining her work.

“He says, that came from the plant,” said Blake. “I’m so sorry. I’ve been watching you, you’ve been working so hard all day and washing the building down, and then this happened.”

Blake has photos of the soot from her property from other instances of coal dust on her property, and pieces of the paper towel she used to clean her property.

She created her own air quality activism group for Springdale residents called Citizens Against Pollution. She would go canvassing or campaigning around the neighborhood, but the group has since disbanded.

Blake now volunteers for the Sierra Club and presented the evidence of coal dust on her property during the public hearing for the new permit for the Cheswick Generating Station in August 2016.

Residents concerned with air quality and people who work for the industrial facility presented their opinions on how the new permit should regulate emissions.

“There had to be over 100 and some people there,” said Blake.

Focus on the Mon Valley

Mark Dixon, setting up his camera equipment to record the Clean Air Rally on March 20th, 2018.

Since moving to Pittsburgh in 2006, filmmaker Mark Dixon always had a creeping awareness of the stench that comes from air pollution. He would jog around Highland Park where he used to live.

“I smelled weird smells, it grew so frequent and I was frustrated by it,” said Dixon. “I didn’t want to jog by an area that smelled of sooty stench”.

His awareness wasn’t fully piqued until he crowdfunded a journey to cover the Paris Climate Agreement as a citizen journalist. He was concerned about climate change and he wanted to find something local.

He chose air quality as his subject because of a March 2016 Consent Order and Agreement (COA) between the Allegheny County Health Department and U.S Steel on air quality violations from the Clairton Coke Works, the number three facility ranked on the Toxic 10 List.

U.S. Steel did not respond to requests for a comment. According to the coke works compliance report, the facility has so far met the requirements from the March 2016 Consent Agreement. They fixed three coke oven batteries and voluntarily added another battery to its compliance plan in June 2017.

Mark Dixon, recording the Clean Air Rally on March 20th, 2018.

There were previous COAs in 2007, 2008, 2011 and 2014. U. S. Steel completed the corrective actions and supplemental environmental project and paid the civil penalty required by the 2007 COA.

The consent agreement stated that U.S. Steel must inspect and fix its coke ovens and come into compliance within 3 years. The facility paid the $3,948,000 of the previous penalties accrued since 2009 and would pay the final $25,000 of the assessed fines.

The agreement came after PennFuture announced an intent to sue U.S Steel for 6,700 violations from January 1st, 2012 to May 31st, 2015. They claimed the nation’s largest coke producer was emitting pollutants that negatively affect health.

Since then, PennFuture announced their “Toxic Neighbor” plan that targets the Clairton Coke Works. The announcement of the consent agreement disappointed Dixon.

“It felt like a breach of public trust and made me deeply question the purpose of the Health Department,” said Dixon. “I decided to start this documentary to get to the bottom of why air quality is a persistent issue in Pittsburgh and immerse myself in the problems and potential solutions”.

That documentary is tentatively called Inversion: The Unfinished Business of Pittsburgh’s Air. His focus for the film is in Mon Valley, close to his home in Squirrel Hill South. The Edgar Thomson Works and the Clairton Coke Works are in that area.

“I’ve been trying all types of things since then,” said Dixon. “From buying and testing citizen science and low-cost monitors to measure particles and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), talking to air quality community members about the challenges, calling the Health Department to talk about air quality problems and ask them questions”.

A common question he has asked is; Where the smell is coming from? Frustrated by being unable to get an answer he decided to use his time and money to research.

“It’s coming from the South or South East. It’s somewhere in between Braddock and Edgar Thomson Mill and the Clairton Coke Works. I can’t pin it down with any factual basis.”

Dixon has tracked weather data, inversion data, and used air quality technology like volatile organic compound (VOC) monitors and particle sensors in his home to find where the smells are coming from.

“I wish that the Health Department would do that work,” said Dixon. “It’s very frustrating that this has not been solved yet, they have worked on this with many more researchers for decades longer than I have”.

“We do know the main sources that are responsible; but since there are also other sources that contribute, we are exploring various means to better understand how much each source emits,” said Ryan Scarpino, Public Health Officer for the Allegheny County Health Department.

Daily White Smoke

Emissions from the Clairton Coke Works seen from outside Cheryl Hurt’s house.

Cheryl Hurt checking her Speck Air Quality Monitor, from the CMU Create Lab.

“That’s what bothers me. That they release this every day,” said Cheryl Hurt. As she looks out the window as the Clairton Coke Works releases white smoke into the air. “I know how harmful it is for us.”

Hurt runs a daycare out of her home in Clairton, a few streets up from the Clairton Coke Works. She understands that emissions today are different from when she was younger.

“The particles that are there now is more harmful now than what we grew up with, there’s an odor that you can smell,” said Hurt. “People who aren’t from Clairton notice the smell, we are used to it”.

A 2018 study from the Surveillance and Tracking of Asthma in our Region’s Schoolchildren (STARS) on children from Clairton Elementary School, found that 18.2 percent of children suffer from Asthma, nearly doubling the rate reported by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Cheryl’s Speck Air Quality meter, reading good air quality in Clairton for that day.

Hurt is aware of the effects and long before reports on the children’s asthma problems were reported, she was trying to mitigate the risk with her Speck Air Quality Meter that she got from the local library.

The device detects and calculates the amount of fine particulate matter in the air. The monitor gives the number of particles in the air, along with a corresponding color, green is good, and red or orange signals poor air quality.

“When it says that it’s bad or moderate, I keep the kids inside,” said Hurt. “I don’t open my windows, it’s usually bad [pollution] outside even when it’s a good day”.

Backyard Woes

John Macus in his backyard in Jefferson Hills.

After a yearlong search for a new house, John Macus and his ex-fiancé purchased their home in Jefferson Hills in 2008 because of the big backyard that came with his house.

“We purchased the home during the recession and he plant was also in the recession,” said Macus. “At the time there wasn’t as much emissions coming from there [the coke works] that time, so there was no way we could see the emissions coming.”

Within the first month of living there, the plant began running again. Macus said he and his ex-fiancé would wake up with shortness of breath, headaches, and migraines.

“When you go outside and ask what’s that smell and how is it getting in the house and the windows are closed,” questioned Macus. “Then you drive by the place and figure out where it comes from, you wonder what did we move next to”?

Macus prides himself on fitness, he runs 15 miles with a 70-pound bag to train for one of his hobbies, Spartan races. The feeling of that training pails in comparison to the symptoms he gets from pollution.

“On the worst days, I feel sick, nauseous, migraines, you feel sluggish, and gasp for air,” said Macus. “. I get winded [from the training], but not like how the pollution gets me.”

He tried calling the Clairton Coke Works to talk about his issues with pollution, the calls would be so frequent, that they started referring him to the emergency services.

“Half of Jefferson Hills Fire Department came once, they brought EMTs and trucks up”, said Macus.

The firefighters came into his house and checked the property with a carbon dioxide detector, instead of one that registers benzene and sulfur.

“The two firefighters stood on my porch, one said he couldn’t smell it, and another said he gets similar smells in his house in Elizabeth”, said Macus.

He realized contacting the Allegheny County Health Department could help him more, so after a year in his house he started contacting them.

They sent him an air quality monitor, and he went out on his porch the next morning and found the evidence he was looking for.

“There was reports of traceable amounts of Benzene and Taurine on his back porch,” said Macus. “There should not be traceable amounts of these chemicals on your porch at 6 A.M.”.

He was frustrated when he reported back to the Health Department what he found. Despite the evidence he found, they couldn’t pinpoint the source.

“There is not a thing around that comes close to it”, said Macus. “That is a giant plant, there are 8-9 giant stacks that do what 10,000-20,000 automobiles don’t even do in one day, it’s so easy to pinpoint.”

John Macus on his porch, looking at his backyard..

“We are continually working with partners and organizations to determine if there is any action that we may be able to take,” said Scarpino. “This is a complicated issue and the question is not one that is easily answerable”.

Macus had attended meetings with groups like PennFuture, GASP, and others, but he wasn’t there for talking, he wanted action.

Along with Cheryl Hurt, he filed a class action lawsuit in May 2017 against U.S. Steel in Allegheny County Common Pleas Court.

They alleged that emissions from the Clairton Plant have affected plaintiffs and members of the putative class of nearby homeowners, allegedly interfering with the use and enjoyment of their properties and causing unspecified property damages.

“It felt like real change was coming when the paperwork was coming through,” said Macus.

The case was filed for consolidation with another case against U.S. Steel, filed in June 2017 by Cindy Ross, a resident from Clairton.

One day, he got a call from one of the attorneys who was representing him, saying that another group of lawyers in the case were not using his complaints.

“When he called me and said [his part of the lawsuit] was falling through, it was heartbreaking.”

Penn’s Future

A sign outside Marti Blake’s house in Springdale, created by the Sierra Club.

The American Lung Association gave the Pittsburgh Metropolitan Area an F rating for air quality and said the air quality in Pittsburgh is not improving on April 18th.

In January, the Allegheny County Health Department’s Air Quality program updated its civil penalty policy so that higher penalties can be levied for violations.

They hope that the higher penalties will act as a deterrent for companies that violate clean air standards and lead to overall improvements in air quality.

Donna Frederick, a Natrona Heights resident, said she only has one request for facilities and organizations involved in the air quality battle.

“I just want to live and want my grandchildren to be able to breathe clean air! It’s a reasonable request.”